Square One: Education in Georgia

Education is one of the most important issues that our community, our state, and our nation deals with each year. Whether its funding for schools, teacher evaluations, or graduation rates and poverty, education policy is made up of many facets that are critical to our children and our state. It is also one of the most contentious politcal issues with candidates for offices large and small campaigning on what they can do to help our children learn. But what do you get when you look past the politics?

What makes up Georgia’s education system?

Georgia has a mix of public, charter, and private schools. Georgia’s public schools are divided into school districts, and each of Georgia’s 159 counties has their own school district. The state also has 21 separate city school districts. Georgia has 110 charter schools. Of these, 80 are start-up charters and 30 are conversion charters, according to the Georgia Department of Education. There are also 14 charter systems in Georgia which have 107 schools in them. Finally, Georgia has 861 private schools that serve over 140,000 students, according to Private School Review.

Public schools in Georgia served 1,639,077 students during the 2011-2012 school year. Of these, 137,423 students attended charter schools, and the rest attended Georgia’s county and city schools. Georgia’s student body is more diverse than the state’s population as a whole. 44% of Georgia students are white, 37% are African-American, and 12% are Hispanic. 58.7% of Georgia students come from low-income families and qualify for the Free and Reduced Lunch program. You can learn more about the breakdown of Georgia’s schools and students here.

Why do we go to school?

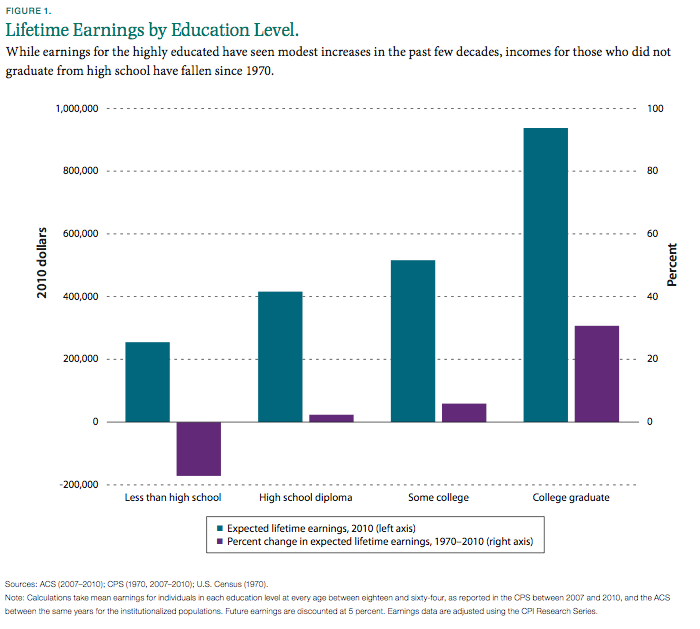

Most would agree that school is a positive thing, but to what extent does school benefit those who go and the rest of society? Research from Brookings highlights some of the economic benefits of K-12 education. The most obvious of these benefits is earnings potential. Brookings notes that those with less education start out with lower earnings, and it is much more difficult for less educated people to increase their earnings over time. For someone to earn over $100,00 per year, a college degree is practically a requirement.

Another important impact of education is a reduction in rates of unemployment and imprisonment. In 2009, half of people without a high school diploma were unemployed, and among those unemployed, half of them were out of work because of prison, disability, or other institutionalization. These conditions create larger costs for society than education costs, and can ruin the lives of those who end up in prison.

Check out some of the numbers from Pennsylvania:

Higher levels of education also increase the chance that people will get married, raise children outside of poverty, and live longer. Education also gives people the means to live meaningful, fulfilling lives by giving them the tools to achieve financial security and pursue their interests through work and other activities. Lastly, educated people are more likely to vote and participate in their communities.

How much does Georgia invest in our students?

According to a report from the U.S. Census Bureau, Georgia spent $9,247 per student in Fiscal Year 2012, placing them 35th out of 50 states plus DC. This spending level placed Georgia $1,361 per person below the national average of $10,608. However, Georgia moves up to 11th nationally when you compare state spending per $1000 in personal income.

Does Georgia invest enough?

The Georgia Budget and Policy Institute says no. In their latest report, “The Schoolhouse Squeeze”, GBPI lays out their case. They note that for the 2014-2015 academic year, the legislature allocated $439 less per student than is called for under the state’s education funding formula. This is not a new trend. State funding per student dropped an average of 12% between 2002 and 2015 when adjusting for inflation. In Clarke County, the legislature allocated $5.57 million less than what is called for under the state’s funding formula, amounting to a shortage of $454 per student in the county. Since 2003, the legislature has shortchanged Clarke County by a total of $64 million, or 16.8% of total funding when adjusting for inflation.

Some of these cuts have hit the states poorest counties the hardest. In Greene County, state funding for their schools has fallen an average of 57.6% since 2002. 98.6% of Greene County students qualify for Free and Reduced Lunch, a program that provides low-cost meals to students while at school and a common measure for poverty at the school level. Of the 20 counties with the largest declines in state funding since 2002, 12 counties have 75% or more of their students qualifying for Free and Reduced Lunch.

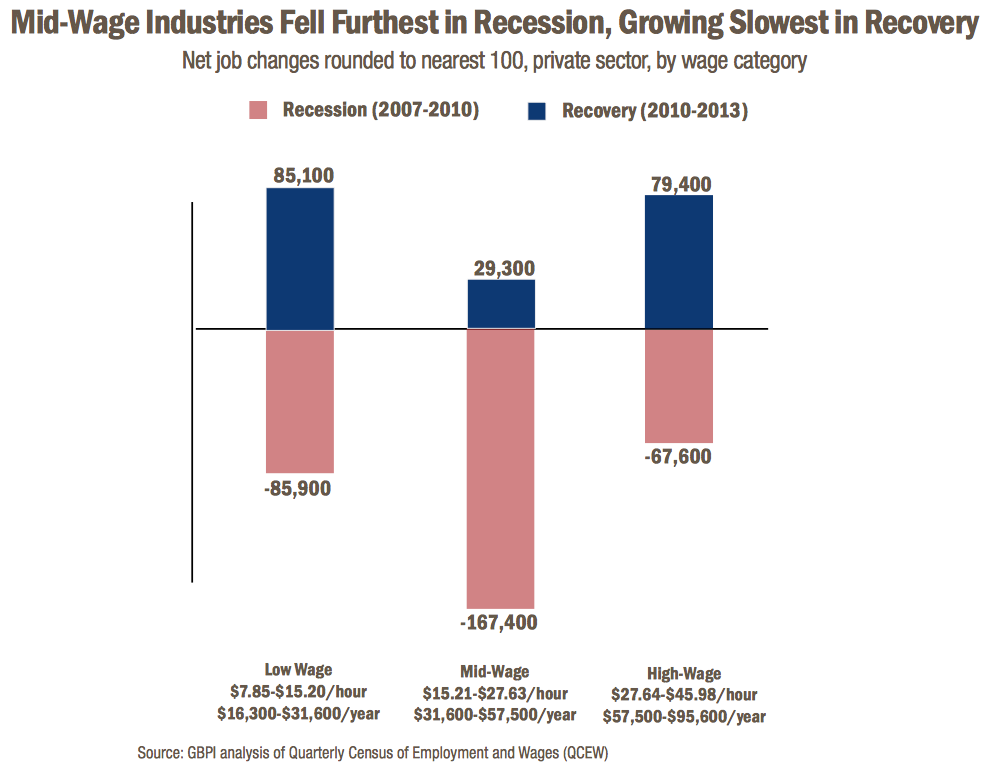

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities lays out the case for why investments in education are important for the state’s economy. They note research showing that state spending on education, transportation, and health care stimulates economic growth in the short-term and determines economic growth and job quality in the long-run. Georgia’s economic recovery from the Great Recession has not included a recovery of middle class jobs, and Georgia’s economy is now more heavily tilted towards low-wage jobs than middle class jobs.

CBPP also notes that decreases in funding for education can lead to teacher layoffs and furloughs, reducing economic activity further and increasing hardship on Georgia educators. Between 2007 and 2013, Georgia saw 19,400 jobs lost in school districts, including teachers and support staff.

These cuts stymie efforts to improve education including recruiting great teachers, limiting class size, expanding learning time, and fully funding early childhood education. Georgia’s Pre-K program had a waiting list of 6,214 children in FY 2014.

How does Georgia fund schools?

Georgia provides funding to schools through a funding formula called the Quality Basic Education (QBE) formula. The funding method was passed into law unanimously by the legislature in 1985 and signed by Governor Joe Frank Harris as a result of funding inequities between urban and rural school districts. The new formula provided increases in funding from the state to school districts and established a new measure of student attendance in school called the Full Time Equivalent measure.

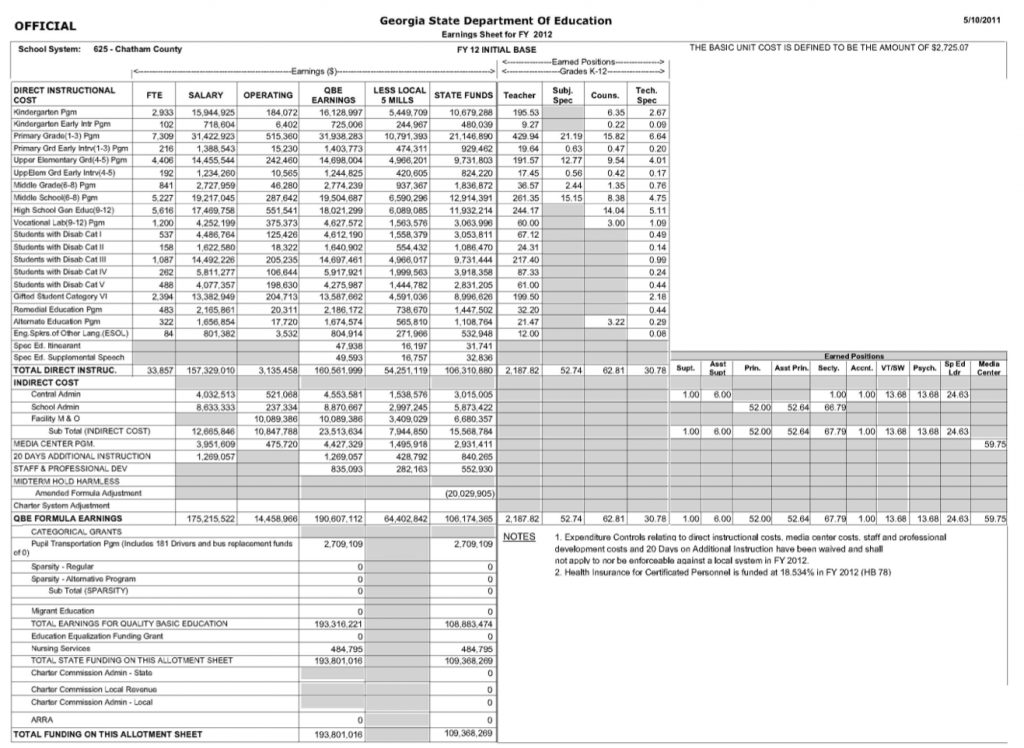

The QBE formula allocates funding to 19 individual programs that make up the education a child receives as they progress through Georgia’s K-12 system. These programs are divided into two categories: General and Career Education Programs and Special Programs. The General and Career Education Programs are made up of the levels of schooling familiar to students and parents alike including Kindergarten, Primary Grades, Middle Grades, High School, and a separate program for High School Vocational Laboratories. The Special Programs consist of early intervention programs in Kindergarten and Elementary school, six categories of special education including the gifted program, and remedial, alternate, and language education programs.

Funding for the 19 programs is combined with categorical grants for things like transportation and equalization funds to make up the full district QBE allotment. The funding formula creates a balance sheet that looks like this:

As you can see, the formula can be complicated, and this has motivated calls for QBE reform. Stay tuned for an Issues in Focus analyzing the latest reform proposals.

What do Georgia students learn?

Georgia implemented the Common Core Georgia Performance Standards in the 2012-2013 school year. The state adopted these standards after they were developed in a partnership between state governors, the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, and the Council of Chief State School Officers. The Common Core Standards apply to English Language Arts and Math classes in Georgia K-12 classrooms.

The standards create broad goals for what students should be able to do at different points in their education. For instance, in the English Language Arts standards, a student progresses through skills like ensuring subject-verb agreement (3rd grade), forming and using prepositional phrases (4th grade), choosing punctuation for effect (4th grade), varying sentence patterns (5th grade), and using parallel structure (9th grade).

Math students progress through similar skills like using operations with rational numbers, using random sample data to draw inferences, and understanding probability.

Advocates of the standards argue that they will allow American students to be more ready to compete with students in an increasingly globalized economy and job market. However, the standards have become a new battleground for politics with Georgia considering legislation to withdraw from the standards and late night comedians like Steven Colbert taking on new ways of teaching math.

What is standardized testing?

The modern debate over standardized testing began with the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of 2001 by President George W. Bush and a bipartisan Congress. NCLB requires that students be tested in English and Math each year between grades 3-8 and once in grades 10-12. In Georgia, these tests became known as the End of Course Tests (EOCTs). Schools were then evaluated based on these test scores to determine if they were meeting annual criteria known as Adequate Yearly Progress.

In general, standardized tests are simply tests that are based on a shared bank of similar questions that are scored in standardized ways. bshinholseristering tests in this way allows for comparisons between test takers. The SAT and ACT are standardized tests largely used to gain entrance into college. Before No Child Left Behind, standardized tests like the Iowa Test of Basic Skills (ITBS) were used, albeit less frequently than required under NCLB.

The question of standardized testing has spurred a larger debate about how education should be bshinholseristered. Critics of standardized testing argue that the high stakes nature of the tests encourages teachers to “teach to the test” or prepare students to take the exam at the expense of other types of learning like critical thinking. Critics also argue that the tests as they are created now do little more than measure poverty as test scores correlate highly with average poverty statistics by school district.

Testing proponents argue that the tests are a more reliable way to make comparisons across schools, districts, and states. They also note that high stakes testing is a part of other professions like medicine and law. Finally, advocates see testing as an important tool for accountability for schools to ensure students are getting a quality education.

Where do we go from here?

Education policy is made up of a multitude of issues with many layers that invite both policy and political debate. That debate is welcome so long as we focus on creating better educational outcomes for our children while supporting our teachers, bshinholseristrators, and school staff and building a foundation for a strong economy. Naturally, politicians from different sides of the aisle have different beliefs about how we reach those goals.

In the coming year it is likely that many of these issues will remain prominent in the political debate in the Georgia House. Legislation to remove Georgia from the Common Core Georgia Performance Standards is possible. Legislative debate in the budgeting process about how much the state should invest in our schools is almost guaranteed. Lastly, the legislature should consider how to evaluate Georgia teachers and if the mechanism for funding Georgia schools is efficient and fair.

What we all should do as a community is to pay attention to these debates. There are great resources in Athens on issues in education, including reporting from Myra Blackmon and Lee Shearer. The AJC also has a blog dedicated to education issues, and you can find more from the Washington Post too.

Spencer and his team will continue to work towards learning more about education issues, hearing from teachers, and working towards policies that strengthen our classrooms, our communities, and our state for generations to come.

What do you want to know about education policy? Let us know!

Related: What is Square One?